Do you ever think about what horses give up in living with us? Humans have a way of always seeing ourselves as the solution, resting confidently in the knowledge that we are their saviors. We have a bank account to prove it. We talk about what they do for us, but rarely consider the cost to them. The courage needed for them to live in our world.

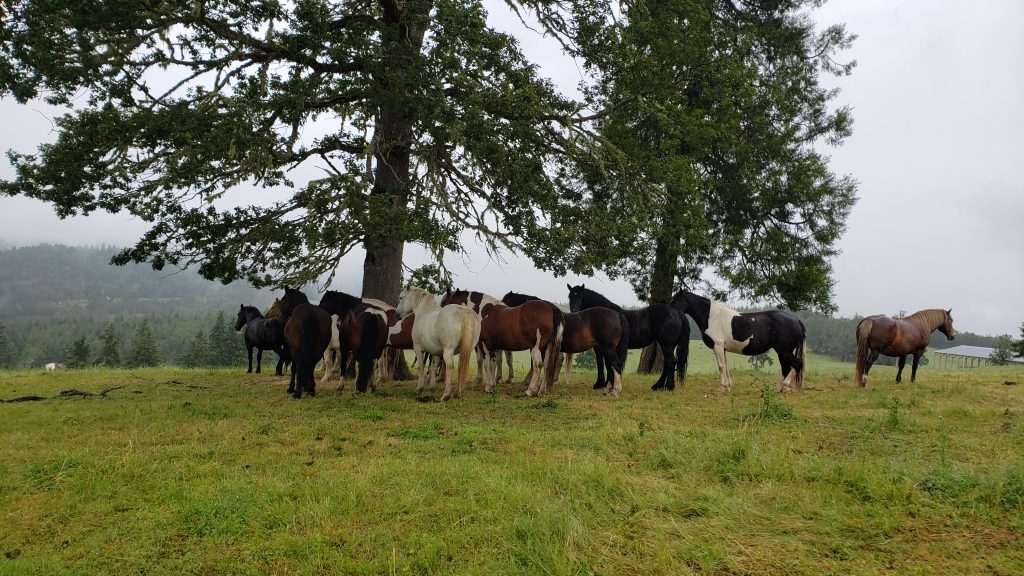

This photo is the big herd at Duchess Sanctuary. I had the extreme privilege of visiting them earlier this year in Oregon. The mares are all originally from the PMU industry in Canada where the pregnant mares stood in stalls with a contraption strapped between their hind legs to collect their urine for the drug Premarin. The industry is closed because the drug ruled unsafe, and these mares and thousands of others bred for this industry were out of work.

Does it sound barbaric? It’s no different than those horses who waited in fire stations for the emergency gallop to fires, those who moved logs to sawmills to build our cities, or those “pleasure horses” who stand in stalls today, spending their lives being our hobby. Relationships are always an exchange of goods and services. That’s what a friend of mine who is a pastor says. I used to fight the notion when I was a young romantic. I see the sense in that now.

Horses and humans have always had a complicated relationship. We love them, we use them. They hurt us physically, and we damage them with poor training and handling. They are a constant reminder of beauty and freedom, of sensitivity and intelligence that is elusive to us; they draw us to them in awe and wonder. And then we make them over to our specifications, controlling their environment, social interactions, and even their eating schedules. We anthropomorphize them into whatever story we want to tell, often ignoring their emotions while dumbing them down to something we understand. We are their guardians. We are their predators.

For their part, horses do volunteer. They are curious about us; they allow themselves to be trained. They have an involuntary instinct to survive; they care about safety. They fear our erratic habits but need the food we provide. We bend close to kiss them and in the next moment, flap arms to get them out of “our” space. We give conflicting signals. Want another example? Horses feel safety in a herd but we ask them to leave and then see their separation anxiety is a training issue. Or when horses stand with their eyes closed and we are certain they are at peace with us, but aren’t closed or partly closed eyes are a calming signal that the horse is pulling inside, evading us by withdrawing?

Our lives with horses can never be unscrambled. Scrolling through the Facebook feed, it’s all right there. Mustangs run over land the cattlemen want for grazing cows. Beloved horses being ridden well. Ranch horses abandoned to starvation and abuse. Humans threatening horses, humans encouraging them. Horses teased for a funny picture.

Back to the Duchess Sanctuary, an upside-down world where horses live the most natural life possible with no work or love required, and free of fussy humans with savior complexes. In sanctuary, horses owe us nothing, not even companionship.

Jennifer and I entered the upper pasture, a vast meadow with groups of mares standing in the shade of trees. Over a hundred and fifty of them scattered, their massive bodies at rest, their tails shooing flies off each other. One mare was apart from the group and down, and as we drew closer, she stayed down. Not normal. The other mares were watching us now, not frightened but also not pandering to us. Their autonomy was regal and glorious. Jen walked an arc one direction, as I stepped the other way for a better angle, knowing better than to think both of us walking quickly up would be helpful.

Just then, a black mare left the shade and walked directly to the prone mare and then turned to face me. I halted. She walked ten yards toward me but instead of sniffing me, she positioned her belly against mine, her body obliterating my view of the ailing mare and Jennifer. Silently, two other mares joined the black mare, stepping up behind me to form a triangle around me, bending their ribcages close enough that I could almost feel each of them with my body. No greeting, they weren’t curious about me. Not friendly and not emotional. They were massive and immobile, and I was contained. My breath stayed intentionally slow and deep as I kept my hands by my side. I did not take a selfie.

A moment later, the mares dissolved back into the herd. I joined Jennifer with their permission. It looked like colic so after a slow polite haltering process, the mare very reluctantly allowed us to lead her to the gate where a sanctuary assistant had pulled a trailer to carry the sick mare to the barn for treatment. There were moments when I wondered if the herd would let her go with us. It ended up being a mild colic, resolved in a few hours, and soon the big girl was returned, healthy and whole, to her herd. She didn’t say thank you and we didn’t expect it.

Horses need us to survive in our world and how arrogant we are to think the life we give horses is necessarily an improvement. We offer horses love, as we claim theirs, but the more I watch and learn, the more I think horses have something better. After all, we fail each other as often as we fail horses. Our culture is nothing to brag about, but remembering those mares, I wonder if horses have had it right all along. It was never about domination, but rather a cooperation.

There is a word in the Maori language that I think might define what horses experience in herds. It isn’t as selfish as individual love but rather lifts the ideal of community welfare:

whanaungatanga – Māori Dictionary (fa-nan-ga-tunga) 1. (noun) relationship, kinship, sense of family connection – a relationship through shared experiences and working together which provides people with a sense of belonging. It develops as a result of kinship rights and obligations, which also serve to strengthen each member of the kin group.

When working with your horse, listening to them in this unnatural world we share, the most important calming signal to learn is their baseline, their resting face. This is it, a herd grazing, breathing together, looking out for each other. This is their normal, beyond the screaming hustling inpatient world with humans. This is their understated natural home, even if they live in cities. If we want to connect with a horse in their language and on their terms, we have to be willing to let go of the things that create noise in our world and in our hearts. It’s an idea as revolutionary as a sanctuary.

We have to let normal be enough.

…

Anna Blake, Relaxed & Forward, now scheduling 2022 clinics and barn visits. Information here.

Want more? Become a “Barnie.” Subscribe to our online training group with training videos, interactive sharing, audio blogs, live chats with Anna, and join the most supportive group of like-minded horsepeople anywhere.

Anna teaches ongoing courses like Calming Signals, Affirmative Training, and more at The Barn School, as well as virtual clinics and our infamous Happy Hour. Everyone’s welcome.

Visit annablake.com to find archived blogs, purchase signed books, schedule a live consultation, subscribe for email delivery of this blog, or ask a question about the art and science of working with horses.

Affirmative training is the fine art of saying yes.

Thank you Anna! This one is so perfectly true, as usual! My riding friends and I just had a very similar conversation while riding down the trail yesterday. We were amazed at how much our horses tell us, if we only stayed quiet enough to listen to them! Your words are always a welcome balm for a frazzled soul every Friday morning.

Thanks, Shauna. Listening is such an art.

Perfect as always, Anna. Learning to be still and actually listen to our horses is one of the best things we can do for them.

For all the folks who think their horse makes funny faces, this. Thanks Carolyn

Wonderful post! Thank you for sharing. The picture became so powerful & moving by the time I finished reading. As a whole, humans really are an arrogant species.

It’s a rare occasion to meet their society so clearly. Thanks Sueann

I so appreciate how you use your skill with words to expand our awareness… of horses and their almost-unbelievable tolerance of us , the lesser species. in my opinion. As a previous comment stated, we humans are so arrogant. I would add we are often deaf by choice and ignorant when it comes to our ‘consciousness’ about our relationships with horses.

Thank you for sharing your experience at the Dutchess Sanctuary. That is surely an awesome place. I cannot even begin to imagine how much work and funds it must take to provide a sanctuary for so many horses.

The place is a living breathing miracle. When the tables are turned in this way, when domination isn’t an option even if we wanted it to be, we really have to rely on them differently. It was magical and it gives me hope, even with the challenges the sanctuary faces. Thanks Sarah

Two days ago, August 19, my Dover left for “greener pastures.” He came to me in 1995 when he was just a young ‘un. For half of his life, I did not know about calming signals. But with the little knowledge I had, I did try to see things his way. For the rest of his time, I believe the little sanctuary we created was adequate for his needs. He was surrounded by his own family of buddies who came and went at their own pleasure — no halters or artificial “aids” to restrain them. For him, as for the many horses who are under our care, how many of us can afford to provide a Duchess Sanctuary; indeed, what would become of them in a world where there is not much “wild” that they can return to. What we can do, it seems, is to educate ourselves the best we can by listening to the Anna Blakes of the world who strive to teach us the way of the horse.

For your years of listening, you gave much. I believe your farm was more than adequate for Dover. You and I both learned by listening to horses. Bless Dover, your good horse and bless you for caring so deeply. Thank you, Lynell for your insightful comments, and thank you for all you did for Dover. Rest now.

So very sorry for your loss of Dover – I also worry because of the lack of “wild” for any of them. It certainly sounds like he had a very good life with you and his buddies – their families mean as much to them – maybe more so – than ours do to us.

I much appreciate you reaching out, Maggie. Firstly, I see I wrote August 19th in error. It was actually August 17th! I agree, we humans could learn more than a lesson or two from the “lesser” species, if only we would dare to listen…

I love this! Almost nothing gives me the worst ice cream headache (other than ice cream) than figuring out in my herd why one is showing juvenile friendliness, openness, and outright happiness to see me while the other has half-closed eyes and looks at me with reservation. One is a three-year-old who only knows his breeder and me and never had a bad experience, the other is a bullfighter from Portugal who obviously has mixed emotions about humans and their existence. I have sleepless nights over trying to find a way to comfort him when he needs it most. Less is more, but we do have a working relationship (“contract”) as he is one of my riding horses and a very fine one, to say the least. Trying to give him comfort while working together is the most challenging thing I have come across in a long time. It took two years for him to not turn away when I entered his field. He shows interest now, even if I show up with the halter. We are making baby steps and he is starting to signal that he may potentially “look into” this human…am I worth his while..? I guess it will be a few years before he feels safe without the need to shut down. So far I have never gotten him into trouble. So far so good. Every day I find myself wondering how many smaller pieces I can break down facial movements and small cues, those almost invisible ones, trying not to miss anything. And then it downright kills me if I did and misunderstood a cue. Something that can surely wreck your day. Thanks again Anna for your many observations and reminders for us! Happy Friday 🙂

Thanks, Susanne. That memory lingers so real to them… how interesting to compare (as anyone must) this pair side by side. You are challenging his history, and that is deep and tiny. Stoic horses will always be my biggest challenge, too.

So, I cried. I am now asking myself why. Probably because in my heart I would like all horses to live this way, and we can wonder out and sit among them sometimes, just to watch and admire. But I know the reality. A non-horse friend was going through a horse magazine I gave him and was horrified to read that an Irish show-jumper was pleased that at a boarding barn in Florida where he was, the horses were given two hours of turnout per day. I am sending an email to the gentleman. Not to be a *&itch or to tell him what a terrible person he is, but to actually inquire as to how he thinks that is beneficial to the horses and then (maybe this is what will get his attention) how it can actually be detrimental to his career! And if he doesn’t think it’s beneficial he should watch the video from Carl Hester about how he runs his farm (spoiler — the horses are turned out — a lot!) So it doesn’t have to be the way so many do it. Maybe one day there will be laws where horses have to be treated in certain ways. I feel there can be a happy middle ground between the wonderful sanctuaries and the horses that are used (and abused) for monetary gain. Mandatory turnout time? Wouldn’t that be wonderful.

I think no turnout is illegal in the EU?? Do I remember that Totalis’ owners got fined for not turning him out? Good luck, Kathy.

Anna you are a master of painting a picture with words; I felt as if I was standing next to you as the black mare approached and her two herd mates flanked you. Reading this piece I was reminded of the old adage “We have 2 ears and 1 mouth; use them in accordance with their numbers”. I have been working hard at being more quiet around my horses, so that I can hear/observe what they’re saying; but I remain all human (unfortunately) and continue to use my mouth like a tool that I can’t put down. Thankfully the horses continue to give me clear feedback and I continue to learn from them (at a snails pace). Thanks as always for enriching the lives of horses by enlightening their humans.

It’s our nature to communicate as we do, changing instinct is hard…. and something we ask horses to do all the time. Thanks for the kind words, Laurie.

It seems to me the Maori meaning of kinship or family connection (whanaungatanga) is much, much closer to equine species than human – belonging & being safe is what a herd or band is all about, right?

Someone there told me this word and it does fit… Thanks Maggie.

Thank you so very much for sharing this with us.

Thanks for commenting. Shelly